India Prime Desk | Devendra Singh

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) World Population Status Report 2025, India’s population has reached 1.4639 billion (1.46 billion) — making it the most populous country in the world.

However, the surprising fact is that India’s total fertility rate (TFR) has now fallen to 1.9, which is below the replacement level of 2.1.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhen and where did the change happen?

This decline has accelerated over the past two decades.

In the 1970s, an average Indian woman gave birth to five children, but by 2025, this number has fallen to less than two.

There are, however, huge differences among states:

Bihar: 3.0

Meghalaya: 2.9

Uttar Pradesh: 2.7

— all still experiencing high population growth,

while Kerala, Delhi, and Tamil Nadu are witnessing population stagnation as people increasingly avoid having children.

Why is the birth rate falling?

The reasons are multi-layered:

Economic insecurity and the rising cost of education and healthcare.

Women’s career priorities and independence.

Urban congestion, housing shortages, and inflation.

Mental stress, pollution, and rising infertility rates.

UNFPA calls this a “real fertility crisis.”

People are not avoiding childbirth because they don’t want children, but because they can’t afford or manage to have them.

How is India changing?

India’s population will peak around the 2060s at 1.7 billion, after which it will begin to decline.

About 68% of Indians are currently of working age (15–64 years) — a demographic dividend that is both a golden opportunity and a major challenge.

India’s future will depend on how effectively it can transform this human potential into employment, innovation, and skill development.

Who is at the center of this transformation?

Young and educated Indians, especially women.

They now want to make their own life choices — when to marry, when (or whether) to have children.

This idea of “reproductive autonomy” is the key message of the UNFPA report — real development happens only when individuals have the power to decide over their fertility, education, and future.

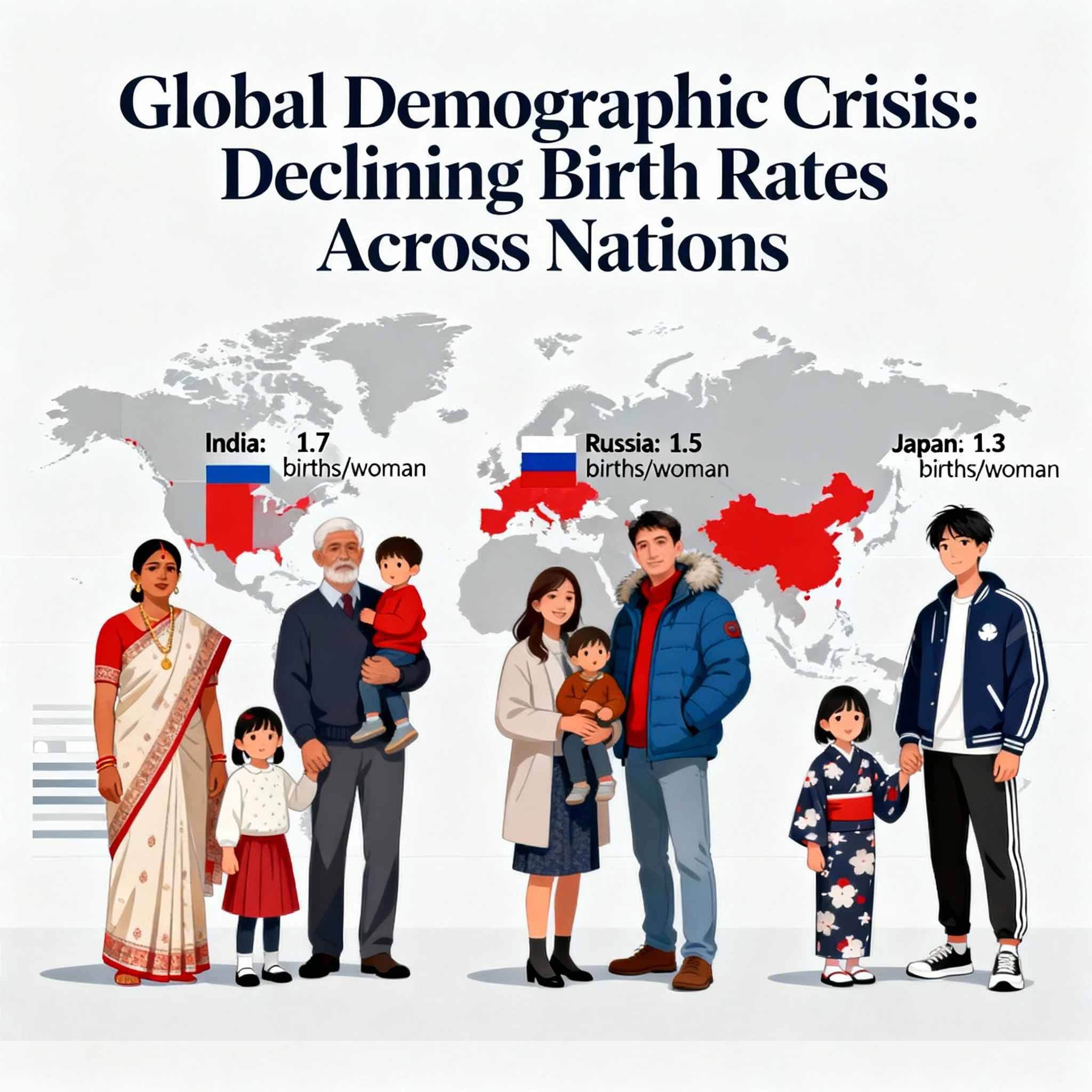

The global picture

Many countries are now facing a “baby bust” — a sharp decline in birth rates — forcing governments to design policies to encourage childbirth.

Let’s look at how different nations are responding.

Japan: “Silent emergency” and doubling the family budget

Japan’s fertility rate has dropped to 1.2, far below the replacement level of 2.1.

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba has called it the country’s “silent emergency.”

The government has launched a three-year acceleration plan that includes:

Increasing child benefits,

Making higher education free,

Providing 100% paid parental leave,

Reforming workplaces to support dual-career families.

Japan is also doubling its family budget and creating a nationwide support system through the Children and Families Agency.

Russia: “Cash for babies” and controversial population push

Russia is facing its worst population crisis in two centuries.

In early 2025, birth rates hit the lowest level in 200 years, with the population declining from 146 million and falling steadily.

The Ukraine war, youth migration, economic instability, and an aging population have deepened the crisis.

President Vladimir Putin has called it a “matter of Russia’s survival” and introduced strict and controversial measures, such as:

Tax breaks for large families,

The revival of the “Hero Mother” award,

Cash incentives even for school and college girls who give birth.

Under the new scheme:

School/college girls receive 100,000 rubles (~₹90,000) for giving birth,

First-time mothers get 670,000 rubles (~₹7 lakh),

Second-time mothers get 894,000 rubles (~₹9.5 lakh).

Critics call these programs morally and socially exploitative, particularly for young girls.

China and Europe: Tax and subsidy models

China has launched a national birth incentive program, offering $500 per child annually, along with daycare reforms and better parental leave.

Countries like Poland, Hungary, and Iceland spend over 3% of their GDP on family welfare programs — including tax breaks, child support payments, and free kindergartens.

In the United States, a “$5,000 child bonus plan” has been proposed to encourage young families to have more children.

Global trends and lessons

By 2050, 75% of countries will have fertility rates below replacement levels, ushering in an era of global population stagnation.

Falling birth rates can lead to:

Labor shortages,

Slower economic growth,

Reduced geopolitical influence.

However, experts say the real solution isn’t financial incentives — it’s ensuring affordable housing, secure jobs, women’s safety, education, and genuine work-life balance.

Having children should not feel like a burden of responsibility, but a conscious and supported life choice.

Conclusion

Countries like Japan and Russia are now in a race to make motherhood financially attractive.

But as experts note:

“Children are not born from economics — they are born from trust and a sense of a secure future.”